Nuremberg: A new kind of justice?

Germany’s surrender on May 7th, 1945 marked the conclusion of World War II in Europe. As Allied forces looked upon the destruction and devastation of the war, they were increasingly convinced that mechanisms must be put in place to hold Axis powers accountable for these atrocities and to provide a unified front to prevent similar violations from occurring again. Outlined in the London Conference, the International Military Tribunal (IMT) was organized to punish Nazi crimes before and during World War II. It consisted of judges and prosecutors from the United Kingdom, France, the United States, and the Soviet Union. Over the course of the next year, these representatives would hold a trial in the German city of Nuremberg, symbolic due to its history as a site of Nazi rallies before the war. The trial, which ended in ten executions, established definitive evidence for Nazi crimes, and set a new precedent for international law and cooperation. Heavily publicized, the proceedings captured the attention of millions, as citizens engaged with ideas and controversy surrounding responsibility, retribution, and justice.

This exhibition presents the 1945-1946 Nuremberg Trial from multiple viewpoints within the Churchill Archives Centre collections. The Centre is proud to hold the personal papers of David Maxwell Fyfe, later Lord Kilmuir, one of the prosecuting counsels at the Nuremberg trial, who served as Solicitor General, Attorney General, Home Secretary and Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, and who played a key role in drafting the European Convention on Human Rights. The Centre also holds the papers of Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, British international lawyer, human rights activist, and judge at the International Court of Justice, who served as a key adviser to the British prosecution team at Nuremberg, and who came up with the concept of crimes against humanity.

Image source: The Papers of Lord Kilmuir, KLMR Acc. 1485 12/1, 1945-1946

BEGINNINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL (IMT)

A draft indictment from September 1945 introduces three offences which would form the legal basis of the tribunal: crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. While the defendants list is left blank, it would eventually include 24 individuals from Nazi political and military leadership. In addition, Nazi organizations such as the Reichstagkabinet, SS, SD, and Gestapo were tried for their role in the war. The final version of the indictment was filed on October 18th, with the trial beginning on November 20th, 1945.

This document is from the archives of Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, a member of the British Prosecution Executive Committee. As a legal scholar, he contributed to international law at Nuremberg through developing concepts such as extradition of criminals, state sovereignty, and the criminal responsibility of states.

Source: “Indictment”, The Papers of Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, LAUT 7/28, 1945

-

“Justice, and indeed ordered systems of justice, are essential prerequisites of freedom, happiness and comfort. Without ordered systems of justice no man or woman can establish his or her rights…It would, in my opinion, be a poor start for the establishment of justice if the most important question of guilt or innocence was decided by the strong hand….The accused should know what is the charge against him and be given an opportunity to make his answer. If these requirements are not present we are helping to create pseudo-martyrs. Instead of consigning them quickly to oblivion, we are raising their memories to trouble ourselves and our children. It would, in my opinion, be a major tragedy in the history of the world if the actions of the Germans were to be allowed to escape in this way from the minds of mankind.”

-

“It is crystal clear that after the League of Nations, including Germany, had declared aggressive war to be a crime on 24th September, 1927, the nations which signed the Pact of Paris, also including Germany, declared aggressive war to be a crime…When a crime has been established there is nothing wrong, in a legal concept or in any other way, in laying down the procedure by which persons will be punished for the crime. Any individual who has participated in the commission of that crime ipso facto becomes answerable personally, and it is the duty, as well as the right, of the nations of the world to find a procedure by which his personal responsibility will be determined.”

“War crimes present no difficulty as it is well settled international law that their perpetrators can be punished by the State whose nationals have been outraged. It would be the apotheosis of illogicality that anyone should escape because he had committed war crimes against the nationals of many States. Similarly, crimes against humanity are merely crimes which have been condemned by every civilised municipal penal law.”

-

“At the end of the war it had extended so widely that there were practically no neutrals left.”

“Despite the magnificent and helpful contribution of electrical science to the problem of simultaneous translation, every additional language adds greatly to the preparation, complication and length of the trial.”

“With regard to German judges there is again the question of whether German lawyers would desire to take part in such a trial, and there is the further more important question that their own actions during the 12 years of Nazi power would make it difficult to escape being branded either as opponents or sympathizers with the Regime.”

-

“The future of humanity demands that such a hearing should be given, that the philosophic basis of the trial is sound, and within the rules founded on that basis every opportunity will be given to the defence to function and for the trial to be fair. These rules are the responsibility of the United Nations. For them we must answer at the bar of history and we can have no argument at the trial whether our basis is right or wrong.”

-

“If defendants are going to be tried they must, as I have said that natural justice demands, know what is the charge against them and have an opportunity of making their defence. A few months is a small price in time for a great contribution to history. We are investigating a conspiracy which lasted quarter of a century. Vast crimes require a big canvas.”

-

“I base the maintenance of the true atmosphere of justice on two things. First, the case for the prosecution depends in the main on captured German documents which are absolutely undisputed. The case against the Defendants is made out of their own mouths. The small part of the case that remains is proved by witnesses who speak on oath of horrors which they have not only seen, but personally experienced. When they have spoken, no-one questions the extent of these infamies. For these reasons Great Britain awaits with quiet confidence the verdict of posterity on her participation in the trial.”

NECESSITY OF THE TRIAL

In the collaboration of many nations and governments, disputes around the novel proceedings arose frequently. Given the scale, significance, and investment in the tribunal, justification of its value to the broader public also became a critical task for its proponents. In his piece, “Socratic Questions,” British prosecutor David Maxwell-Fyfe speaks to an imagined audience, addressing common questions about the trial’s logistics and legitimacy. See the major themes in the toggle menu to below:

“The Nuremberg Trials. A Socratic Analysis of the British Approach,” by David Maxwell-Fyfe, The Papers of Lord Kilmuir, KLMR 7/4, 1946

SETTING THE STAGE

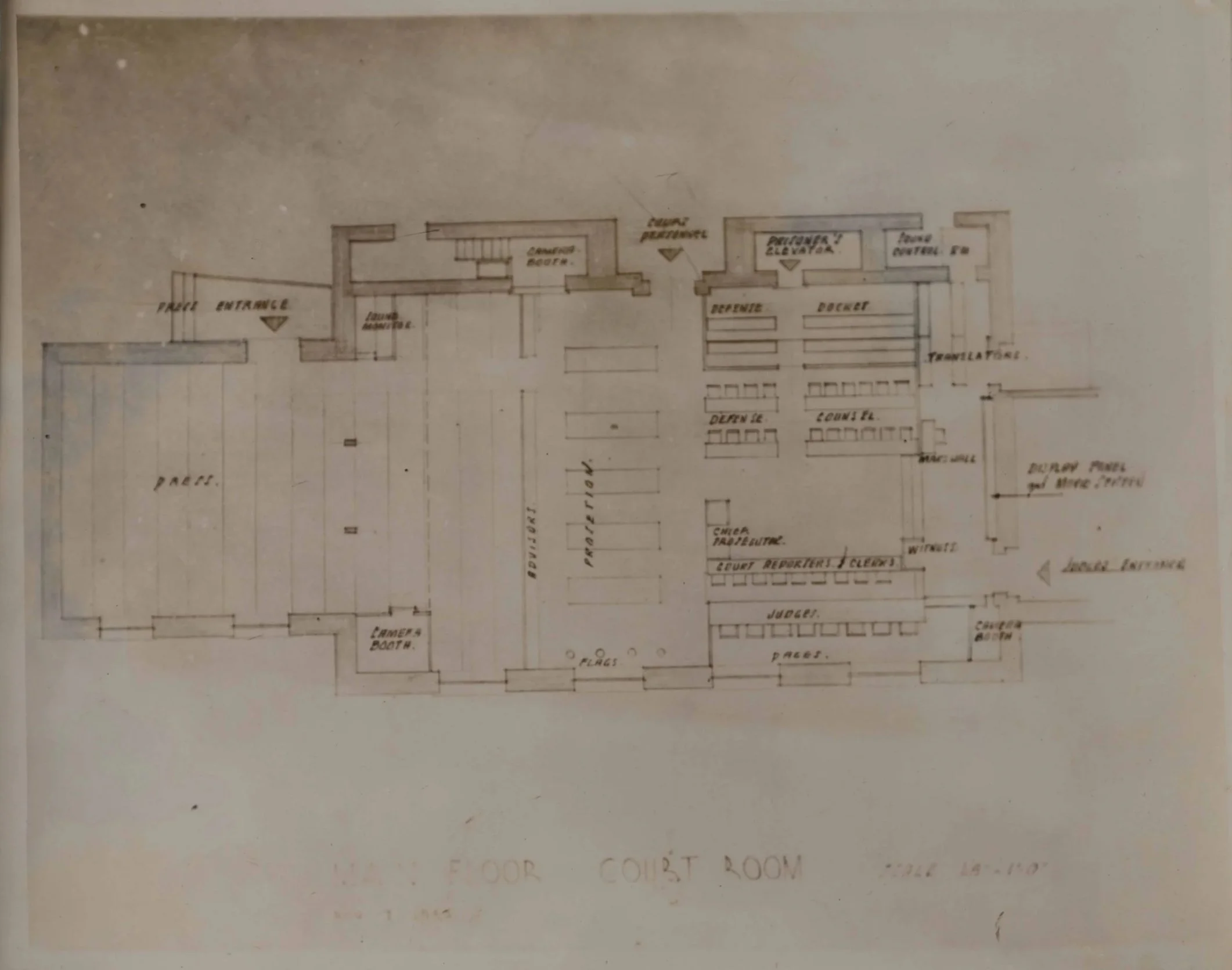

The multinational cooperation of the International Military Tribunal necessitated detailed planning. The Nuremberg Palace of Justice was refurbished by the Americans to accommodate large crowds of lawyers, staff, military, journalists, and spectators.

The Palace of Justice, showing damage from the war, but relatively intact. "Then to see old town, obviously once a most beautiful place. Now, one-third mere rubble, four-fifths of the remainder completely gutted” —Arthur Salter in “Salter Diary,” SALT 1/15, 1946. Image source: KLMR Acc. 1485 12/1

Courtroom blueprints showing seating assignments, KLMR Acc. 1485 12/1.

The courtroom under construction. “A gloomy room in dark brown paneled wood; grey curtains. Three doors each with mottled grey marble at side & above with shields & figures above. Only artificial- neon lights from ceiling giving effect of daylight.” —Arthur Salter in “Salter Diary,” SALT 1/15, 1946. Image source: KLMR Acc. 1485 12/1

Infrastructure was also built to support a team of simultaneous interpreters; a method pioneered at the proceedings. Participants and spectators wore headsets to hear coverage in English, French, Russian, or German. Image source: KLMR 5/4

BEHIND THE SCENES

This letter from British Prosecutor David Maxwell-Fyfe in November 1945 illustrates the shambolic nature of early preparations for the tribunal. The proceedings took over nine months, due to the massive quantity of documents that needed processing, and the difficulties of reconciling different prosecution styles.

Image source: KLMR Acc. 1485 1/1

“Enormous quantities of whiskey and Vodka are drunk in the Bars, there is dancing every evening, everything is in full swing. All the world seems to have arranged a rendez-vous at Nuremberg” – Curt Reiss in “The Trial Goes On,” KLMR Acc. 1512 1/1, 1945.

Moving to Nuremberg for the duration of the trial meant much went on outside of courtroom hours. Colleagues and friends were united around shared social experiences, and the prosecution took part in drinking, dinner parties, and dances.

While the prosecuting committees enjoyed the prestige and connections this provided, socializing and grand occasions drew critical attention to the trial. The lavish events took place in a world still desolate and hungry.

Image source: KLMR Acc. 1485 12/1

LIMITED ACCESS

To protect the safety of the tribunal, visitors and participants were required to carry proper documentation. Passes of David Maxwell-Fyfe, British prosecutor at Nuremberg are shown below.

“Nuremberg swarms with American Military Police and security precautions are everywhere in evidence. Passes to the Court of Justice have to be produced, not once, but at several barriers, and at one of the controls I was called on to furnish a specimen signature for comparison with the one on my identity card”—Kenneth White in “The Master Swingers of Nuremberg,” MISC 100

Image source: KLMR Acc. 1485 3/2

Strict security measures meant accessibility proved particularly difficult for German citizens and journalists:

“There are not many Germans in the Court House, only a few charwomen, messenger boys, porters, waiters, etc. who have all been most carefully screened before being employed.…Since the Germans can now not even get near the Court House, much less into the Court Room, it appeared all the more necessary to offer the Germans a specially detailed and comprehensive reportage of the Trials…. But when the Trials started, there was not a single German Reporter present. German News Agencies were represented by American and English persons who sent short, factual reports, reports which naturally did not do justice to the German point of view.” ––Curt Reiss in “The Trial Goes On,” KLMR Acc. 1512 1/1, 1945.

LARGER THAN LIFE

The Nazis on trial were a great source of intrigue and sensation. As a result of the war, much of the public was already familiar with the more infamous defendants. Some were eager to see retribution, mocking their frustrations or appearance. Others were curious to understand the Nazi psyche, and how these men could have committed such horrible acts. Photographs, cartoons, and reports flooded from the courtrooms to keen audiences abroad.

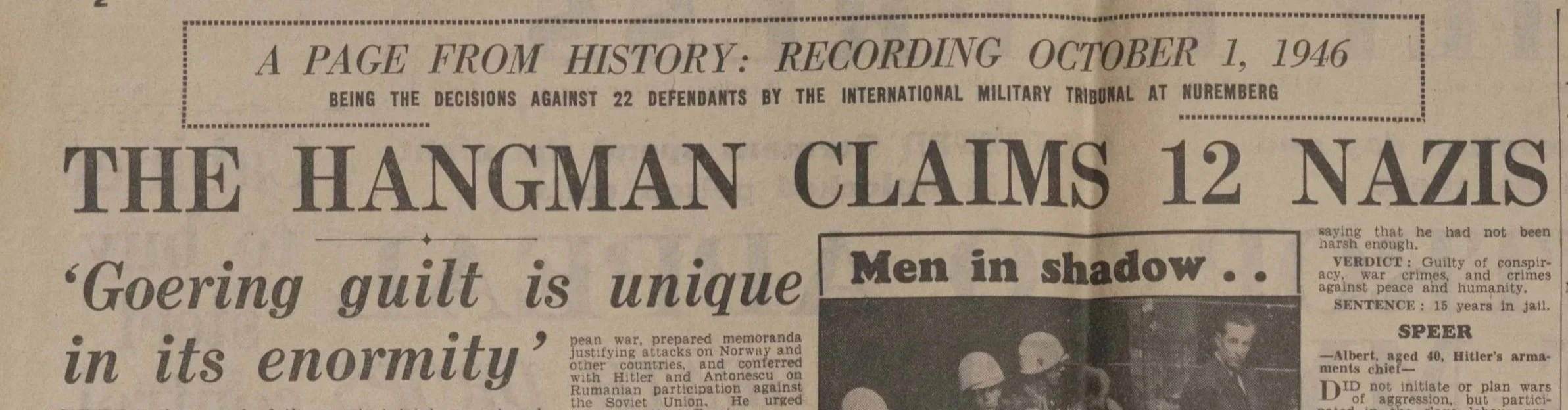

These newspaper headlines from 1946 colour the trials with dramatic flair, especially giving coverage to reactionary stories, or stories outside of the courtroom. The defendants are mocked for their rage, anguish, or stupidity.

Image source: KLMR 2/5-6, 1946

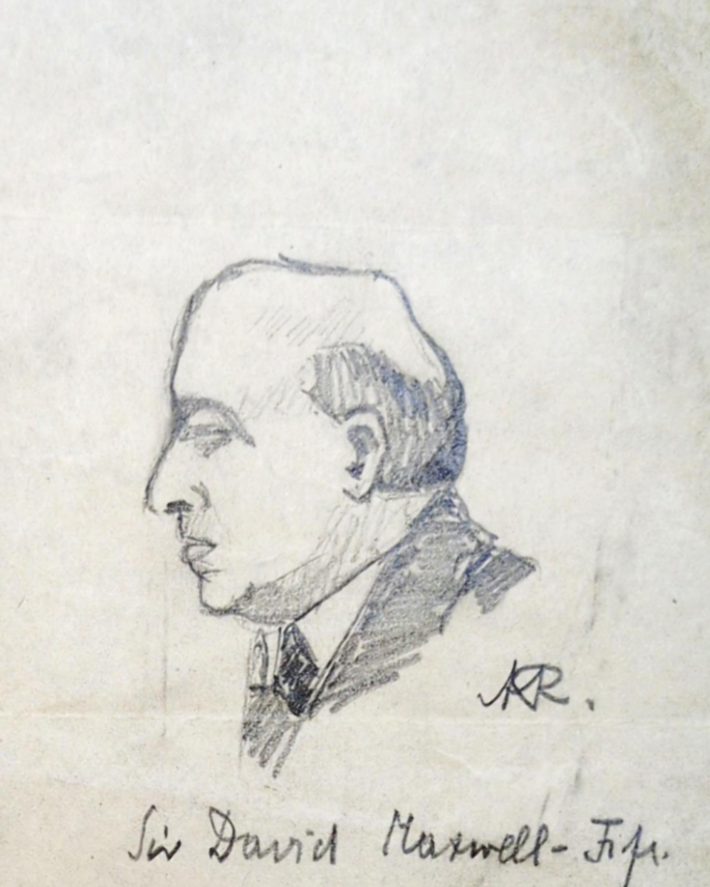

The press were not the only ones keeping a record. This sketch of David Maxwell-Fyfe, British Prosecution, was drawn by the defendant Alfred Rosenberg. Rosenberg was a Nazi theorist and philosopher, later hanged at Nuremberg after having been found guilty on all four charges.

Image source: KLMR 7/4

EVIDENCE AND SENTENCING

The prosecution relied heavily on documented evidence: memos, correspondence, maps, and reports. In the defendants’ own words, these papers charted the planning and execution of aggressive war and crimes against humanity. In addition to documents, prosecution sometimes utilized witness testimony and photographic or video evidence, especially to showcase the atrocities of Nazi concentration camps.

The prosecution gave its closing arguments at the end of August 1946. After reconvening, the judges announced sentences on October 1st. Twelve of the defendants were sentenced to death by hanging, seven to imprisonment in Spandau prison, and three acquitted.

“Is this a trial the main object of which is to take the lives of these defendants? What are the lives of these twenty defendants put against the lives, the agony, the torture, the suffering, and the humiliation of the millions which they sent to their doom? It is only by an ignominious and malevolent corruption of language that one can speak of revenge in a case such as this. Revenge implies some proportion between punishment and crime. There cannot be such proportion in this case.” —Prosecution Speech: Part 3, LAUT 4/37

Image source, right and underneath: KLMR Acc. 1485 12/1, KLMR 7/3

NUREMBERG IN RETROSPECT

The trials marked a final chapter in the horrors of World War II, and the coming of age for international law. For the prosecution, it was an era that promised future peace, responsibility, and cooperation.

“I want to see what I think is the inalienable heritage of every human spirit translated into an enforceable minimum standard for Europe. It has often been said that barbarism is never behind us but always below is. I can think of no better way of preventing its rising again” —David Maxwell-Fyfe in “United Europe and the Individual,”KLMR Acc. 1512 2/2

Image of Prosecutor Robert Jackson, Judge Robert Falco, and Prosecutor David Maxwell-Fyfe touring the Nuremberg facilities. KLMR Acc. 1512 1/3, 1945.

“If the conditions of humanity are going to improve there must be more international working legal processes. For this, I believe Nuremberg was a happy augury. The four nations of the prosecution co-operated and, I think, the Defense counsel trusted us. Faced with a concrete task the United Nations were united. The extension of this phenomenon is the hope of a stricken world” —David Maxwell-Fyfe from “Nuremberg in Retrospect,” KLMR Acc. 1485, 3/1, 1947.

“A new epoch is opening in human government with the rights and duties of the individual in the very centre of the constitutional law of the world. But these new mansions of faith, progress and order will not be built on secure foundations until the impersonal sovereignty of the law has, through this Tribunal, pronounced judgement upon these authors of the greatest evils and the greatest crimes yet inflicted by human beings upon their fellow men.”—Prosecution Speech: Part 3, LAUT 4/37

EPITAPH ON NUREMBERG

However, the tribunal was not without controversy, and many voiced their dissatisfaction with the proceedings. Author Harold Montgomery Belgion was appalled by the treatment of the German defendants and opposed their death sentences. In his books, Epitaph on Nuremberg and Victors’ Justice, he brands the trial as hypocritical. While there was ample evidence of Allied forces committing war crimes, none were brought to trial. In addition, prosecution and judges only came from the victorious nations.

The book resonated with many religious leaders and concerned citizens. It also found resonance with Nazi sympathizers, such as the imprisoned Fritz Hauff, who created a handwritten German copy, pictured next to the original below.

“I believe your book to a very powerful plea for the recognition that principles to which most us would still be anxious to subscribe are in fact slipping from us. Your documentation is admirable and places clearly before me what I had myself suspected and suggested privately to others during the trial: the anomalous position of the tribunal and the suppression of similar “crimes” on the side of the victors…”

“I am glad you should have published the book. […] As I see it, the future will pay for Nuremberg, and pay heavily. The most disturbing fact about it is that so few people appear to have been disturbed by it.”

—Personal Comments addressed to Montgomery Belgion, BLGN 4/11

Image sources, left and right: BLGN 4/28 and BLGN AS/1

LONGEVITY OF JUSTICE

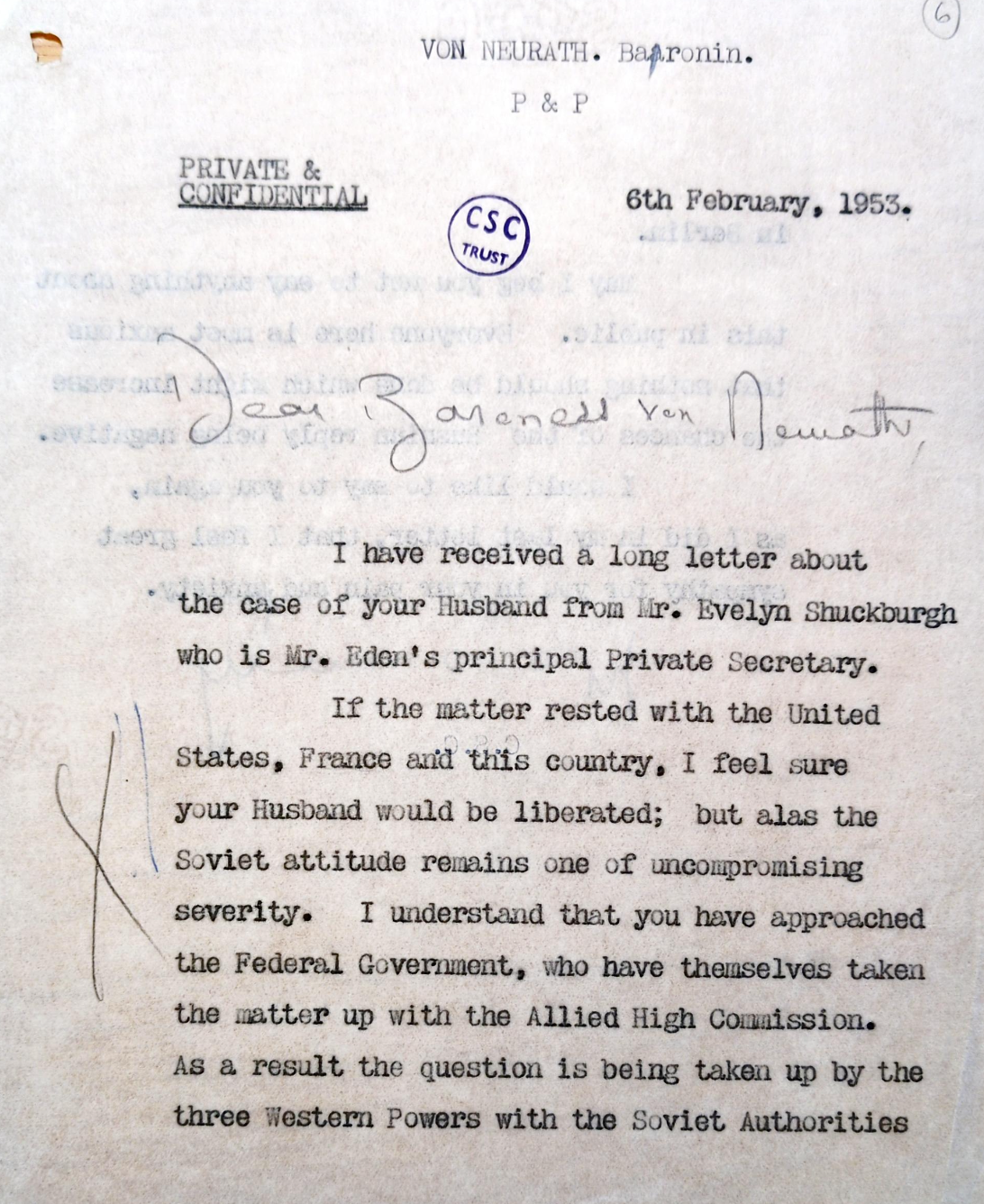

Years after the verdict, imprisoned defendants made pleas for early release. Baroness von Neurath wrote to Clementine Churchill, begging for her husband’s sentence to be reduced. In the letter to the right, Clementine Churchill responds, showing sympathy for the Baroness’s situation while expressing the political difficulties of the request. Von Neurath was eventually released in 1954, due to ill health. Several other convicted criminals had their sentences reduced, with the hope of fostering better relations with the West Germans during the Cold War. Lead largely by the Americans, this pattern of leniency was especially opposed by the Soviet Union and members of the prosecuting committees. While controversy persisted over maintenance of the expensive Spandau prison, it continued to house IMT criminals until the death of its last inmate, Rudolf Hess, in 1987.

“By acting as if they were treating as a matter of political expediency the continued enforcement of judicial sentences passed upon war criminals, the authorities of the United States lend colour to the otherwise utterly false accusations that these sentences were no more than vengeance wreaked by the victors upon the defeated…The policy of releasing war criminals appears to many to be so much at variance with the maintenance of the authority of international law and public morality that it renders altogether irrelevant the question whether it is likely to bring some practical advantage by recurring the support of the German people in any emergency that may arise.” —Hersch Lauterpacht to Justice Robert Jackson, LAUT 1/68, 1951.

Image source: The Papers of Clementine Churchill, CSCT 3/86

CSCT 3/86

CLOSING

The 1945-1946 Nuremberg trials were just the beginning of prosecuting international war crimes. Trials of Japanese leadership took place in Tokyo soon after, and Nazi defendants continued to be tried in Germany for the coming decades.

As cold war tensions stalled global cooperation, it seemed unlikely that such trials would be a frequent occurrence. However, following genocide in Yugoslavia and Rwanda during the 1990s, two further criminal tribunals have taken place. Since 2002, the international criminal court (ICC) has been active in prosecuting violations of international law, though its jurisdiction remains unrecognized by the United States, Russia, and other global powers. Despite violations of international law both during and after World War II, none of the victors at Nuremberg have been prosecuted and found guilty of war crimes.

Media coverage was active at Nuremberg, bringing transparency and intrigue to an engaged public, and supporting reaction or debate. New media and technology have continued to develop, connecting groups and movements around the world. In our time of heightened conflict, these communication tools have become platforms of discourse as many rally for stricter, more just, or more transparent international criminal proceedings. At the same time, they have opened pathways of propaganda and misinformation that can obstruct the truth.

“What is important to humanity is not the sufferings but what it learns by those sufferings; yet too often such learning has been obscured by dispute and doubt. If, as I believe, there has been presented by the prosecution an indisputable and objective basis on which justice may be sought, then mankind may well hope that when she is found and has given her answer, whatever that may be, Justice will remain among men”

—David Maxwell-Fyfe in “The Importance of the Nuremberg Trial for Germany,” KLMR Acc. 1485 3/1, 1946.

While Prosecutor David Maxwell-Fyfe held high hopes for the trial to set a precedence of lasting justice, 80 years on, it seems Nuremberg’s significance lies not in the answers it provided, but the questions it proposed. The debates set in motion at Nuremberg regarding global conflict and resolution remain contentious to this day:

How do we hold individuals accountable for mass-atrocities?

How can international proceedings be made democratic and transparent?

Who controls international law, and are they immune to its jurisdiction?

How can nations with conflicting interests collaborate to sustain security and peace?

This exhibition has been curated as part of the Archives Centre’s project: Nuremberg 1946-2026, commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Nuremberg trials. Further resources can be found in the Churchill Archives Centre’s collection, or by using the Nuremberg Research guide.

This exhibition was researched and presented by student bursary holders from Churchill College, Phoebe Pryce-Boutwood & Helen Brozovic.