One series, eight volumes, two treatments

Treating a series of photo albums with leather or with Japanese paper

Introduction

The Papers of Reginald Brett, 2nd Viscount Esher, an historian and Liberal politician, are stored at the Churchill Archives Centre and are essentially related to his life and career except a small part that belonged to his wife, Eleanor Frances (died 1940), or Viscountess Esher: 8 beautiful photo albums from the beginning of the 20th century.

Very little is known about Eleanor but the way she created these scrapbooks says a lot about her creativity, her love for history and her documenting skills. She glued and cleverly attached documents from the First World War including powerful photographs of soldiers in the trenches, letters, dried flowers in envelopes, illustrations and her personal notes written as a diary.

Description and condition of the bindings

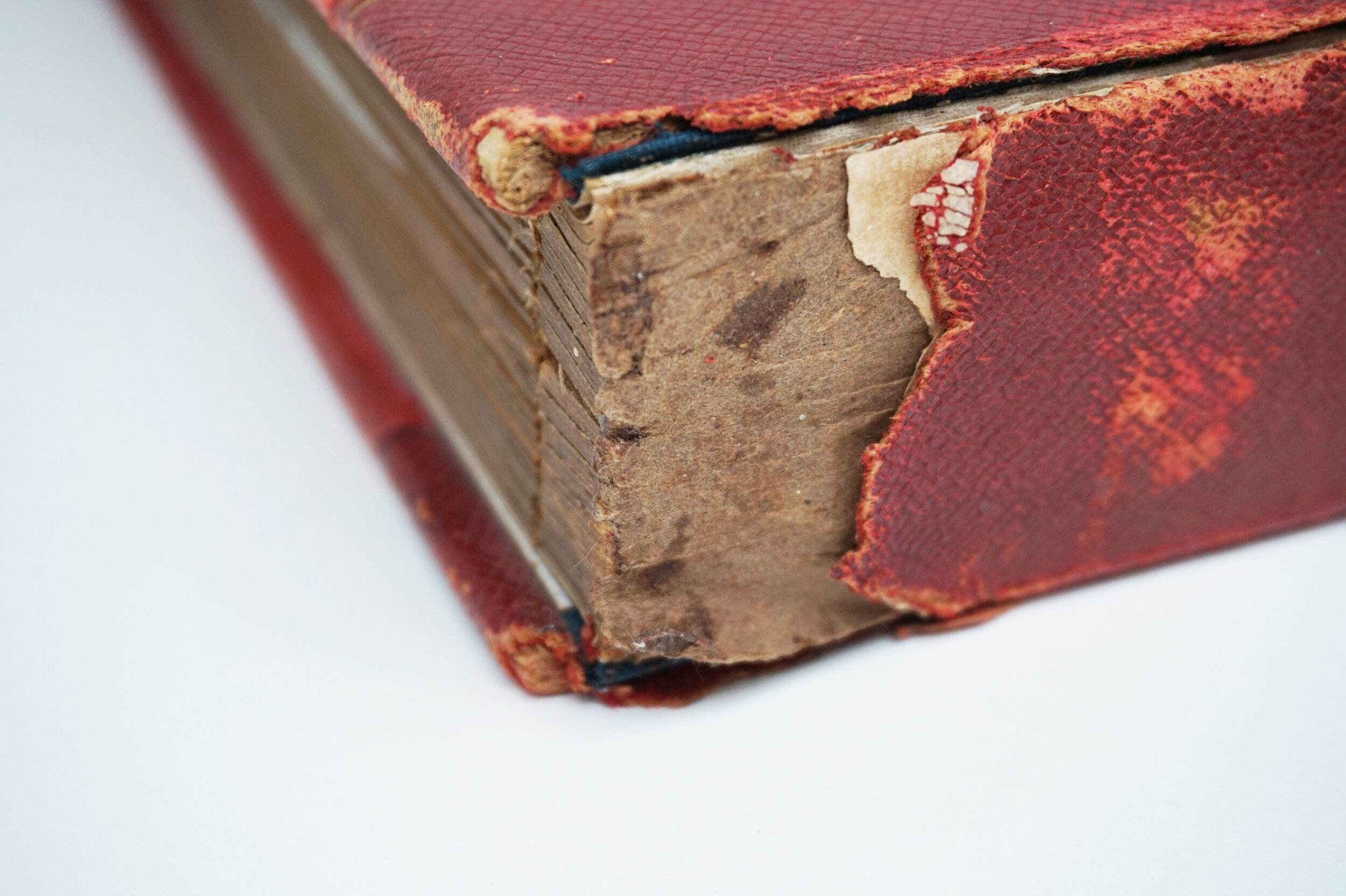

All bindings were covered with cloth on the boards and leather on the spines. The majority of the joints were broken or partially broken.

The back was hollowed – the leather was not attached directly on the back of the text block but moved away from it when opening the book thanks to what we call a hollow. Several leather spine were completely lost and the others were damaged especially at the caps and joints.

The back of the text block was probably sized with animal glue and lined with brown paper and mull (loose textile material). All three materials were oxidised (acidic and weak) and the mull was broken on both joints except in one case.

The thick folios were not sewn but held together only thanks to the sizing and lining on the spine. The boards were originally only attached with the mull, the spine covering and the inner joint making the attachment very weak. Indeed, even if all boards were still attached, some of them were only held by the inner joint (paper). The heavy weight of each of the volumes increased the risk of damage as they were all difficult to handle.

In their current condition, no researcher could have access to them so a conservation treatment was necessary.

Treatment

When treating an object, it is important to respect the history and the structural properties of the object. But what do you do when the original features can be harmful for the good conservation of the object? In the 19th and 20th centuries, binders often created weaker bindings in order to reduce the cost of the manufacturing process. The Esher volumes were made in that period; they didn’t have a strong board attachment and the text block was not even sewn.

The eight volumes could be separated in two categories: the ones with an original leather spine and the ones without one.

When the spine was completely lost, we decided to change the original properties of the spine as we did not see the benefit to re-create a hollow for several reasons. An original hollow back (B on the image below) is great to reduce tensions on the leather spine and is therefore interesting when the original spine is decorated or fragile, but in this case the original spine was absent. On the other hand, a tight back binding (A on the image below) - where the leather is adhered to the spine - not only reinforces the back of the text block but also consolidates the attachment of the text block to the boards. Therefore, we created tight back bindings with a new strong archival vegetable tanned leather for volumes with the spine missing.

For the other category, when the original spine was still present, a new hollow (120 gsm archival paper) was applied on the back, not only to recreate the original structure but also to reduce constraints on the fragile 100 years old leather.

A new hollow (made with a 120 gsm archival paper) was created and pasted on the volumes that had their original spine. For this category of damage, it was not necessary to fill the losses with leather, an expensive material which is time-consuming to apply.

Instead, we used toned Japanese paper lined with aerolinen which gave some texture to the Japanese paper. The filling was applied only on the necessary areas (see image below), then the original spine was pasted back on.

Where the spine was damaged, pieces of toned Japanese paper lined on Aerolinen were applied with wheat starch paste. The textile not only reinforced the joints and endcaps but it also gave a nice texture to the surface of the Japanese paper in order to visually blend with the original textured leather.

When the spine was completely lost, a large piece of calf leather was applied directly on the sanded archival paper. This consolidated the binding even more and gave the volume a completed look.

When dried, pieces of toned Japanese paper were pasted at the exact shape of the losses to level up the filling. Finally, the same Japanese paper was applied on top overlapping the edge of the losses and on the weaker parts of the joints – including where the grain layer of the leather was missing – for reinforcement, protection and aesthetics.

Cross-section of the treatment on volumes with their original spine still present.

Cross-section of the volumes missing their original spine.

Finishing

Applying toned Japanese paper filling on the damaged leather for protection, consolidation and aesthetics.

Conclusion

It was interesting to divide the whole series in two categories in order to find the most appropriate treatment for all of the bindings while still keeping the same overall aesthetic for the whole series.

If the conservation treatment of five of the volumes is now completed, three more volumes need to be treated but the project was put on hold because of the lockdown. The treatment will start over as soon as we are back in the building and when the project ends, our researchers will be pleased, I am sure, to find objects containing so much interesting and valuable information.